By Patrick Adams – New York Times

With the announcement in April that the Zika virus spreading across Latin America can cause microcephaly in the womb, leaders across the region have come under increased pressure to relax some of the world’s most restrictive laws against abortion.

Only two countries in Latin America have made abortion legal and widely available. Cuba was the first, in 1979; Uruguay the second, in 2012. But it’s the experience of the latter, one of the most democratic countries in Latin America, that offers a lesson in reform — or at least a picture of what is possible.

It started 10 years before the law was passed, with a medical protocol called the “Uruguay Model.” Described by its architects as an “intermediate step” toward allowing abortion, the protocol was designed to make safer the many abortions then being carried out clandestinely.

Indeed, by the late 1990s, unsafe abortions were a leading cause of maternal mortality in Uruguay, accounting for nearly 30 percent of maternal deaths. Nowhere was the problem more pronounced than at the Pereira Rossell Hospital, Uruguay’s main public maternity hospital, which serves a primarily low-income population in the capital, Montevideo. There, nearly half of all maternal deaths were because of unsafe abortions, and in 2001 a group of gynecologists, psychologists, midwives and social workers decided to act.

“The situation was dramatic,” recalls Dr. Leonel Briozzo, Uruguay’s vice minister of public health. Then an adjunct professor at the University of the Republic, Briozzo led the group, called “Iniciativas Sanitarias,” in a pilot program at Pereira Rossell with one aim: to provide women contemplating an abortion with judgment-free, factually accurate information on, among other things, the use of medicines to terminate a pregnancy.

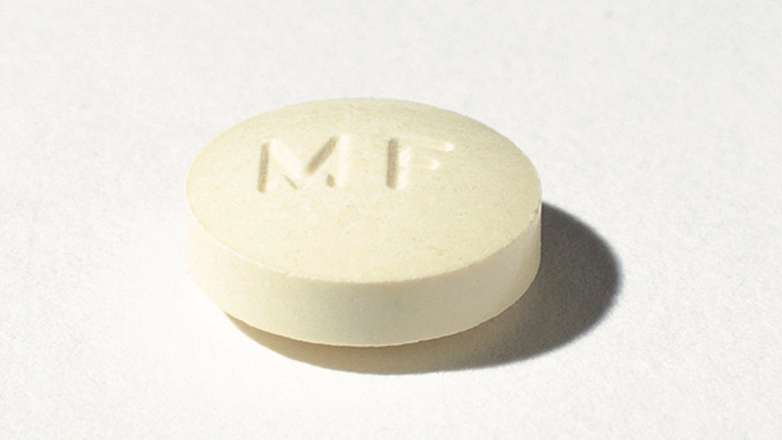

As in other countries where abortion was criminalized, women in Uruguay had turned to the drug misoprostol (Cytotec), which was originally developed as an anti-ulcer therapy. When Cytotec arrived on the market in 1985, the drug’s maker, Searle, hoped it would lead a “product flow renaissance” — a grand plan to revitalize the company’s flailing pharmaceutical business under its president at the time and chief executive officer, Donald Rumsfeld, who had been President Gerald Ford’s secretary of defense and would later return to that position under President George W. Bush.

Little did Searle foresee that, to women with only limited control over their reproductive lives, the warning on the label — “Cytotec should not be taken by pregnant women” — would prove to be better marketing than any ad campaign. It hinted at a chance worth taking, and when it was found to be safer and more effective than other back-alley procedures, the pill’s popularity exploded.

In Cytotec, millions of women suddenly had access to an inexpensive, over-the-counter option for privately terminating a pregnancy and making it look like a miscarriage. Rumsfeld’s company had inadvertently armed the poor and disenfranchised with a powerful new tool — the kind of technology that could cause a revolution.

Governments responded by limiting sales of the drug to hospitals or pharmacies registered with local authorities. Some states in Brazil banned misoprostol entirely. And while women could (and did) continue to obtain misoprostol on the black market, studies suggest that they used it with little knowledge of proper dosing or routes of administration, side effects or follow-up care. Some reported confusing misoprostol with other pills, like emergency and oral contraceptives.

“Misoprostol use in the clandestine practice of abortion has largely developed on a trial and error basis,” Joanna N. Erdman, assistant director and MacBain Chair in Health Law and Policy at Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University, wrote in a 2011 article in the Harvard Journal of Law and Gender. The question, she added, was “how to reach women with safer-use information in restrictive legal environments.”

The Uruguay Model offered a way forward

Inspired by needle exchange programs aimed at preventing the spread of H.I.V. through injection drug use, Briozzo and his Uruguayan colleagues took a so-called harm reduction approach to the problem, framing abortion as, first and foremost, a public health concern. While acknowledging the penal code’s prohibition of abortion as a crime in their country (with exceptions in the case of rape and incest and to preserve the health of the woman), they posited that abortion has a “before” and an “after,” and that, during these periods, health care providers were obliged to intervene.

At a “before visit,” a physician would confirm a pregnancy and its gestational age, identify any pathological conditions, and determine whether the woman qualified for a lawful abortion. If she did, abortion services would be rendered upon request. If not, the physician would provide the woman with an evidence-based overview of different methods of clandestine abortion; the risks associated with each method and their legality; alternatives to abortion, and available social support should the woman decide to continue the pregnancy.

Though the physician would explain how to correctly use misoprostol, he or she would provide no information on how or where to obtain the drug, because doing so was against the law. “It was not advice,” says Erdman. “It was not prescribing or promoting,” and it was this, she says, that allowed the Uruguay Model to operate within the law.

In a 2006 paper on the pilot program, Briozzo and colleagues described the “before visit” as an “opportunity for women to be seen as citizens, with rights, who should be provided with information that guarantees that they will be in a better position to take the best decisions, according to their own situations, environment and values.”

All women who attended the “before visit” were encouraged to come in for an “after visit,” for either prenatal or post-abortion care, depending on what they chose to do. For those who had chosen to have an abortion, the physician would “with absolute confidentiality” confirm complete termination of the pregnancy and address any complications. Uterine aspiration would be performed on women with an incomplete abortion. And all women would be offered contraception.

Out of 675 women who attended the “before visit” between March 2004 and June 2005, 495 returned for the “after visit.” Of the 439 women for whom there was information, almost 90 percent had decided to terminate their pregnancies, all of them by using misoprostol. (The rest had chosen to continue the pregnancy, had not been pregnant in the first place, had miscarried, or had met the requirement for a lawful abortion in the hospital.)

Source: New York Times