In terms of progressive ideas, Uruguay has always punched above its weight. It introduced a free, universal public education system in 1878, 40 years before the United States. Eventually, Uruguay blossomed into one of the most robust social welfare states in Latin America, with the region’s lowest income inequality. It was the first country in the world to legalize recreational marijuana and the second in the region to legalize gay marriage, after Argentina.

This small country of 3.5 million people has also burnished its environmental credentials, conserving native forests, protecting biodiverse areas and striving to be carbon neutral by 2030. Few countries have demonstrated a comparable commitment to reducing emissions. Beyond lowering emissions of methane, a harmful greenhouse gas, from livestock and increasing forest coverage to promote greater carbon sequestration, Uruguay has radically transformed its energy grid.

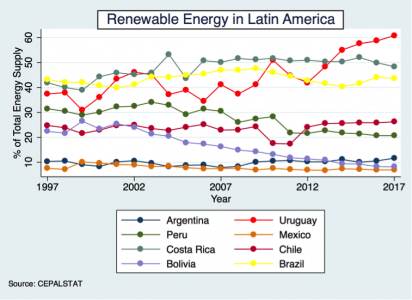

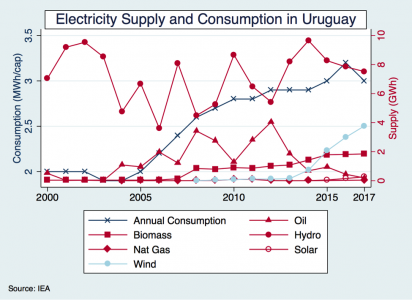

Since the signing of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, hailed as the first major international treaty on climate change, Uruguay’s aggregate renewable energy supply has grown by 93 percent. According to the International Energy Agency, only Denmark, Lithuania and Luxembourg are more reliant on wind and solar power. Between 2008 and 2017, Uruguay went from having virtually no wind power to nearly 4,000 megawatts of installed capacity. Emissions have fallen roughly 20 percent from their 2012 peak.

Uruguay’s successful shift to renewables was spearheaded by the leftist Broad Front coalition—the Frente Amplio, or FA—which controlled the national government for 15 years until last month. A new center-right president, Luis Lacalle Pou of the National Party, was sworn in on March 1 after narrowly winning election in November. But Lacalle Pou’s government is unlikely to drastically reverse Uruguay’s shift to renewable energy. By building a broad consensus with a wide range of national and international stakeholders, the FA adopted an inclusive strategy for energy transformation that will be difficult to undo. Its playbook offers a model response for other countries seeking to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels.

Uruguay’s shift to renewables dates back to a serious drought, which began in 1997 and lasted until 2007, and cut existing hydroelectric generation in half. The government tried to cover that sharp decline in power supply by increasing oil imports from Argentina, but at a steep price. In 2006, Uruguay imported 75 percent of its energy needs. Growing energy demands triggered blackouts, and carbon emissions skyrocketed.

The crisis made political elites recognize the need to increase domestic energy-producing capacity. In 2005, President Tabare Vazquez took office for the first time. With a strong environmentalist faction, the FA saw a solution to the overlapping dilemmas of energy security and environmental sustainability: more wind turbines and biomass facilities.

The government needed to act decisively and invest in the future. As one of the principal architects of the program and the former national director of energy, Ramon Mendez, wrote in 2014, “Everything happened because we did the opposite of the traditional parties. We made the state proactive and did not sit and wait for the market to respond.”

While executive decrees jumpstarted this shift to renewables, Vazquez’s government did not act in isolation. Despite enjoying majorities in both house of the legislature, it called on other parties to forge a consensus. In 2008, Vazquez convened the Multiparty Energy Commission, including all opposition parties and a former president from another party, Jorge Sanguinetti. The commission produced an accord for energy development promoting diversification, increasing efficiency and reducing oil imports. Over the next decade, key legislation sailed through the General Assembly with broad support.

The government simultaneously held events with business associations to provide information and facilitate links between the public and private sectors. In consultation with international experts and local businesses, the government rolled out market-friendly measures to encourage and protect private investment in green energy.

Contracts included a 20-year price guarantee with a requirement for the state to purchase all wind-generated power. To reward speed, the government paid higher rates for projects completed before 2015. Afterwards, pricing fell from $110 per megawatt-hour to around $65 to $85 per megawatt-hour. From the government’s perspective, either price represented significant savings compared to energy generated from imported oil, which hovered between $200 and $250 per megawatt-hour.

By building a broad consensus with a wide range of stakeholders, Uruguay adopted an inclusive strategy for energy transformation that will be difficult to undo.

Price stability coupled with low maintenance costs meant projects were profitable and attractive to multinational wind power firms like Nordex and Vestas. But rural farmers and other stakeholders were able to buy stock in the projects, and a 20-percent local content requirement for inputs meant some profits remained in the country.

While increasing domestic energy supply, the government made a social commitment to universalize access and lower energy costs for Uruguayans in the most precarious circumstances. Consulting with civil society groups and sharing information also mitigated potential resistance to the new wind farms.

Scientists from the Universidad de la Republica, the country’s oldest and most prestigious university, were closely involved in this transformation. A wind tunnel was built on campus to test turbine designs and topographical positioning. In 2009, the university produced a national survey outlining areas with significant wind potential—the blueprint for future projects.

Uruguay cooperated with international organizations during the policymaking process, too, which allowed it to overcome institutional, financial and technological barriers. Complementing a $1 million grant from the Global Environment Facility, an independent financial organization with ties to the United Nations and the World Bank, Uruguay co-financed $6 million to construct an initial 5 megawatt wind farm in 2007, which increased local expertise and provided a template to showcase the future. The wind farm also helped spark interest among private investors and landowners, while building broader social acceptance. Considering the billions of dollars in investment that flowed into the country afterward, this first modest investment sparked huge dividends.

The government hoped to have 300 megawatts of wind power online by 2015. It wound up with more than 700 megawatts in 2014, with more to come. By 2018, 49 wind parks were completed, with 700 turbines and a total capacity of 3,775 megawatts. Despite a retooled natural gas thermal plant with Hyundai that came online in 2016, the government continues phasing out costlier and dirtier oil-burning facilities, only two of which remain active in the country. The state energy company highlights the source of its electricity online every 24 hours, and on many days, the renewable portion surpasses 95 percent.

Uruguay does have some of the highest energy costs in South America, at roughly 20 cents per kilowatt-hour, which is still cheaper than most countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. But the country is also a net exporter of electricity, which it sells to Argentina and Brazil.

When the political winds changed in Montevideo last November, Lacalle Pou’s margin of victory in the presidential run-off against the FA’s Daniel Martinez was only 37,000 votes, the closest since Uruguay’s return to democracy in 1985. The FA remains the largest party in both the upper and lower houses of the General Assembly.

Lacalle Pou’s campaign concentrated on rising crime and fiscal moderation. As a candidate, he promised to further develop the energy sector and encourage research, but his true feelings about sustainability and renewable energy are largely unknown. So far, his nominees to key government posts have been technocrats. While dramatic divergence from the past is possible, it seems unlikely. His National Party participated in the wind farm revolution and celebrates Uruguay’s shift to clean energy. While lowering costs should be a priority for the new government, renewable energy is here to stay.

The takeaways from Uruguay’s energy makeover are clear. To transform national energy grids that are dominated by fossil fuels, crises are useful, but only if governments show the commitment for real change. The FA constructed a broad coalition of government officials, political parties, the private sector, scientists, civil society and the international community. Such a coalition can make a dramatic shift possible, but also ensure that it lasts.

“Transformation happens with people, not against people. You cannot impose reforms from the top,” Mendez, the former national director of energy, mused in a television interview in 2014. “You have to involve and include people in the transformation,” he added. “Point the ship in the right direction and have a little patience and continuity.”

Written by Grant Burrier, an associate professor of politics and history at Curry College in Massachusetts. He writes extensively on Latin American politics, political economy and environmental policy.